The Dream of a Floating Palace

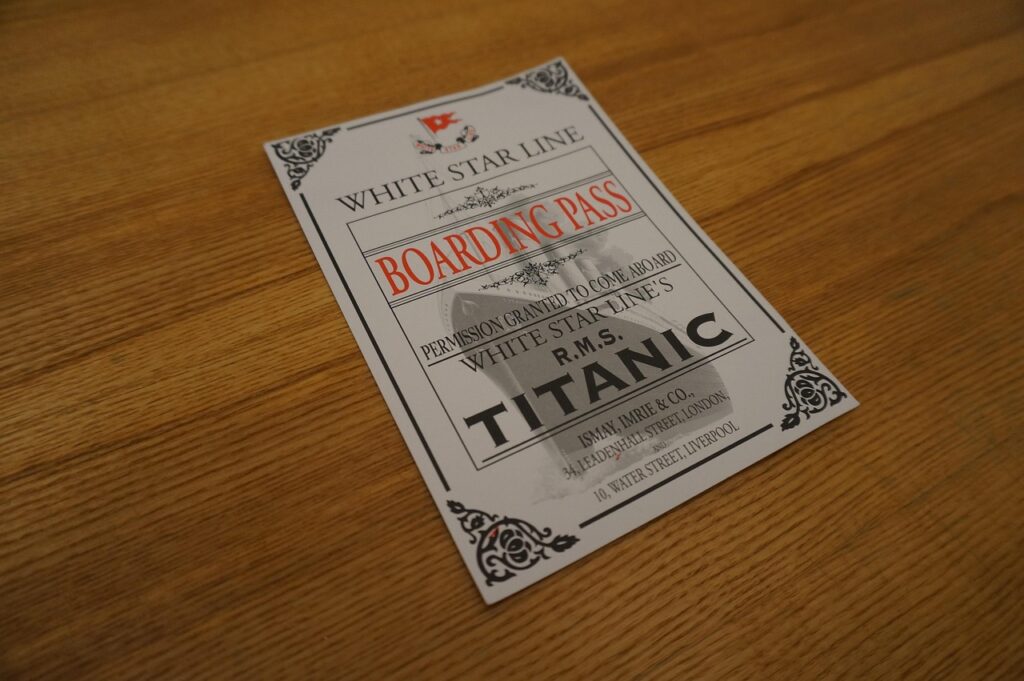

At the turn of the twentieth century, transatlantic travel was highly competitive. Shipping companies competed fiercely to build the largest, fastest, and most luxurious ocean liners. The British company White Star Line sought to dominate the luxury market rather than focus solely on speed. Titanic Pride and Disaster To achieve this goal, they commissioned three massive ships: Olympic, Titanic, and Britannic.

Belfast’s Harland & Wolff shipyard is where the Titanic was built. Measuring about 882 feet long and weighing over 46,000 tons, it was one of the largest moving objects ever built at the time. The ship boasted grand staircases, elegant dining salons, a swimming pool, a gymnasium, and even Turkish baths. For first-class passengers, it offered comfort comparable to the finest hotels on land. It carried more than 2,200 people, including passengers and crew, on its maiden voyage.

Although often described as “unsinkable,” Titanic was never officially labeled as such by its builders. However, it did incorporate advanced safety features for its time, including watertight compartments designed to prevent catastrophic flooding. Ironically, these very features contributed to a false sense of security among passengers and crew.

The Maiden Voyage

On April 10, 1912, Titanic departed from Southampton, England, bound for New York City. It made brief stops in Cherbourg, France, and Queenstown (now Cobh), Ireland, to pick up additional passengers. On board were some of the wealthiest individuals in the world, ambitious immigrants seeking a new life in America, and hardworking crew members responsible for operating the massive vessel.

The ship’s captain, Edward Smith, was an experienced and respected officer. The journey across the Atlantic began smoothly, and the atmosphere on board was festive and optimistic. However, wireless operators received multiple warnings about icebergs in the North Atlantic shipping lanes. Despite these warnings, Titanic maintained a relatively high speed, partly because calm seas made icebergs more difficult to spot.

The Collision

Late on the night of April 14, 1912, lookouts Frederick Fleet and Reginald Lee spotted an iceberg directly in Titanic’s path. Despite an immediate attempt to turn the ship and avoid a direct collision, the iceberg scraped along the starboard side of the hull. The impact occurred at 11:40 p.m.

The damage proved fatal. Several of the ship’s watertight compartments were breached. Although the ship was designed to stay afloat with up to four flooded compartments, the iceberg had opened at least five to the sea. Water poured in steadily, and it soon became clear to the ship’s designer, Thomas Andrews, that Titanic would sink.

Chaos and Courage

As the severity of the situation became apparent, the crew began launching lifeboats. Unfortunately, Titanic carried only 20 lifeboats—enough for about half of those on board. At the time, maritime regulations were outdated and based on a ship’s tonnage rather than passenger capacity. Many lifeboats were initially lowered only partially filled, as passengers struggled to grasp the seriousness of the situation.

The policy of “women and children first” was largely followed, especially in first and second class. However, the social divisions of the era were evident. Many third-class passengers faced language barriers, locked gates, and confusion that delayed their access to lifeboats. As a result, survival rates varied sharply by class.History of titanic.

In the early hours of April 15, Titanic’s bow sank deeper into the icy waters. At approximately 2:20 a.m., the ship broke apart and disappeared beneath the surface of the Atlantic Ocean. The frigid water claimed the lives of around 1,500 individuals.

Rescue and Aftermath

The nearest ship to respond to Titanic’s distress signals was the RMS Carpathia, commanded by Captain Arthur Rostron. Arriving around 4:00 a.m., Carpathia rescued over 700 survivors from lifeboats. The survivors were taken to New York, where news of the disaster shocked the world.

Public inquiries were held in both the United States and Britain. These investigations led to major reforms in maritime safety. Lifeboat requirements were increased to accommodate all passengers, and continuous radio monitoring became mandatory. In 1914, the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) was established to improve maritime regulations.

Discovery of the Wreck

The Titanic’s final resting spot was a mystery for many years. In 1985, an expedition led by oceanographer Robert Ballard discovered the wreck nearly 12,500 feet below the surface of the North Atlantic. The ship lay in two main sections, surrounded by debris scattered across the ocean floor.

The discovery reignited global interest in Titanic. Artifacts recovered from the wreck—ranging from personal belongings to pieces of the ship itself—provided powerful connections to the people who had traveled aboard her. However, the recovery efforts also sparked debates about preservation and respect for what many consider a maritime grave.

Titanic in Popular Culture

The Titanic disaster has inspired countless books, documentaries, and films. The most famous adaptation is the 1997 film Titanic, directed by James Cameron. The film combined historical events with a fictional love story and became one of the highest-grossing films of all time. It introduced a new generation to the tragedy and reinforced Titanic’s place in global culture.

Beyond entertainment, Titanic continues to symbolize both technological ambition and human fragility. It serves as a reminder that even the most advanced creations are subject to the forces of nature.

A Lasting Legacy

More than a century after its sinking, Titanic’s story still resonates. It represents an era of confidence and industrial achievement, but also the consequences of overconfidence and insufficient safety precautions. The lessons learned from the disaster reshaped maritime law and saved countless lives in the decades that followed.